Sorry to say I didn't win this. They estimated the daggers value of being $2500-4000...so I didn't even try. Wish I could of past this on to someone else but I just found this auction and didn't catch the deadline, and I been extremely busy taking care of a family emergency. Sad really because this dagger was mislabeled and the item sold for $750. Says it sold "on the floor" and the buyer had to also pay a buyers premium($146), plus taxes and fee...all in all +$1000 out the door. With the estimated price range they gave, I thought that is where they start...I never used Rock Island auction so I didn't even know they start the auctions off at $1. As you can see from the photos, this one is exceptional. The designs are typical, but the ivory handles really sets this dagger apart from all others...rare to see any Filipino(non-Moro) style blade with ivory. I hope to God the buyer/collector knows what he got. It would be extremely sad to know this piece of Philippine history went to a buyer who goes on with the rest of his life thinking it is an early American Masonic dagger from the 1830s.

Sorry to say I didn't win this. They estimated the daggers value of being $2500-4000...so I didn't even try. Wish I could of past this on to someone else but I just found this auction and didn't catch the deadline, and I been extremely busy taking care of a family emergency. Sad really because this dagger was mislabeled and the item sold for $750. Says it sold "on the floor" and the buyer had to also pay a buyers premium($146), plus taxes and fee...all in all +$1000 out the door. With the estimated price range they gave, I thought that is where they start...I never used Rock Island auction so I didn't even know they start the auctions off at $1. As you can see from the photos, this one is exceptional. The designs are typical, but the ivory handles really sets this dagger apart from all others...rare to see any Filipino(non-Moro) style blade with ivory. I hope to God the buyer/collector knows what he got. It would be extremely sad to know this piece of Philippine history went to a buyer who goes on with the rest of his life thinking it is an early American Masonic dagger from the 1830s. A society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in.

Thursday, December 2, 2010

1898 República Filipina Dagger Lost

Sorry to say I didn't win this. They estimated the daggers value of being $2500-4000...so I didn't even try. Wish I could of past this on to someone else but I just found this auction and didn't catch the deadline, and I been extremely busy taking care of a family emergency. Sad really because this dagger was mislabeled and the item sold for $750. Says it sold "on the floor" and the buyer had to also pay a buyers premium($146), plus taxes and fee...all in all +$1000 out the door. With the estimated price range they gave, I thought that is where they start...I never used Rock Island auction so I didn't even know they start the auctions off at $1. As you can see from the photos, this one is exceptional. The designs are typical, but the ivory handles really sets this dagger apart from all others...rare to see any Filipino(non-Moro) style blade with ivory. I hope to God the buyer/collector knows what he got. It would be extremely sad to know this piece of Philippine history went to a buyer who goes on with the rest of his life thinking it is an early American Masonic dagger from the 1830s.

Sorry to say I didn't win this. They estimated the daggers value of being $2500-4000...so I didn't even try. Wish I could of past this on to someone else but I just found this auction and didn't catch the deadline, and I been extremely busy taking care of a family emergency. Sad really because this dagger was mislabeled and the item sold for $750. Says it sold "on the floor" and the buyer had to also pay a buyers premium($146), plus taxes and fee...all in all +$1000 out the door. With the estimated price range they gave, I thought that is where they start...I never used Rock Island auction so I didn't even know they start the auctions off at $1. As you can see from the photos, this one is exceptional. The designs are typical, but the ivory handles really sets this dagger apart from all others...rare to see any Filipino(non-Moro) style blade with ivory. I hope to God the buyer/collector knows what he got. It would be extremely sad to know this piece of Philippine history went to a buyer who goes on with the rest of his life thinking it is an early American Masonic dagger from the 1830s. Monday, November 29, 2010

Interview with Congressman Henry Allen Cooper (1926)

Article written in 1952 by a Filipino who accidentally stumbled across Congressman Henry Allen Coopers office while working at the US Capitol building at Washington back in 1926. For those that do not know of Henry Allen Cooper, he is the author of The Philippine Bill of 1902, The Organic Act, or the Cooper Act of 1902. This Bill establishes the Filipinos own Bill of Rights, instills 2 representatives in US Congress, and establishes the Philippine Assembly(our own House of Representatives) whom are elected by Filipinos. A key note about the story of this bill prior to its passing, Congress was split on Coopers bill and it was on the way to being shot down. In a last ditched effort to garner support for his bill, Cooper took to the floor and fought for this bill in front of Congress. To end his debate he read Jose Rizals "Mi Ultimo Adios" with tears in his eyes. Coopers speech and the reading of Rizals poem was met with cheers and applause. The Cooper bill passed.

Philippine Organic Act 1902

http://www.chanrobles.com/philippinebillof1902.htm

RIZAL IN THE AMERICAN CONGRESS

December 27, 1952

By Vicente Albano Pacis

IN the semi darkness of the ground floor of the US Capitol in Washington, I entered an office by mistake—and stumbled upon the author of the Philippine Bill of 1902—and an interesting episode in Rizalian lore.

It was 1926. Though perhaps not as critical as that of 1902, the American congressional situation with respect to the Philippines was serious. In Manila, General Leonard Wood, the Governor-General, and Manuel L. Quezon, the Senate President, were in the midst of a knock-down-and-dug-out fight. And friends of the general on Capitol Hill were active. One of them, tough and determined Congressman Robert Bacon of New York, had introduced a bill separating Mindanao and Jolo from the Philippines and retaining them under US sovereignty, should Luzon and the Visayas become independent, Senator Sergio Osmeña has rushed to Washington in alarm to try and block the shocking proposal.

A young Associated Press correspondent, I was closely watching the developments on the measure and was that day on my way to the office of Congressman Kiess of Pennsylvania, chairman of the House Committee on Insular Affairs, when I entered the wrong door. I was about to withdraw, having started to offer my excuses, but what the elderly female secretary said rang a bell in my head.

She said. “This is the office of Congressman Henry A. Cooper; can I help you?”

“Cooper of Wisconsin?” I inquired.

I had been in and out of the Capitol for five or six months and had not heard any mention of his name now seen him in the house session hall. I had no idea that he was still a member of Congress. But feeling sure now that the man into whose office I had gotten by mistake was none other than the man for whom the Cooper Act—the first Philippine Organic Law—was named, I decided to see him. I asked the secretary if I could do so.

She slipped into the dim inner office and almost right away came back to usher me in. Seated beside an ancient roll-top desk, the completely white-haired, short, thin old man trembled visibly as he rose slowly and offered me his hand.

“I’m Cooper,” he stated simply.

I explained who I was and added for its possible psychological effect that I had just left the University of Wisconsin the previous summer. But it was not necessary. The mere fact that I was a Filipino seemed to have had a tonic effect on both his strength and memory.

“Well, sir, so you’re from the Philippines?” he said in a reedy voice as he motioned me to a seat.

Having himself sunk back into his swivel chair, he continued, “I’m always glad to meet Filipinos. In all modesty, one of the highlights—one of the most thrilling moments—of my long congressional service was my participation in the drafting and enactment of the first enabling act for the Philippines. And, sir, President McKinley, Governor Taft, and the rest of us met obstacles on every side. But do you know who came to our rescue, sir? None other than you great martyr and hero, Jose Rizal.”

I had gone in, glad of the opportunity to meet a history-book name. His reference to Rizal left me in a state of trembling expectation. What he did next heightened the suspense.

He leaned back in his chair, pressed interlaced fingers on his breast and closed his eyes. He remained thus for some time. I began to wonder if he had gone to sleep as old people often do at the oddest moments. I was about to call his secretary when he suddenly opened his eyes, sat erect, gripped the arms of his chair with each hand as if he had just remembered something very important. His mind had evidently traveled some two decades back, and now he resumed talking.

“Philippine-American relations started very badly, sir!” he recalled. “Those of us who were trying to formulate what might be a just and wise Philippine policy were harassed on every side. Do you know, sir, that President McKinley finally had to resort to nightly prayer?”

With a faraway look in his eyes, he related how the president, criticized on all sides and offered conflicting advice, had finally decided to go on his knees every night in the White House. And one night there had come to him what appeared to be the ultimate solution of the situation. Give back the Philippines to Spain? Leave them to another power in the Orient—Germany, Great Britain, Japan? Abandon the Filipinos? Each of these questions had brought an unsatisfactory answer. So the president had inescapably reached the decision that the only honorable course left to America was to take over the Philippines “to civilize, to educate and to train in self-government.”

The old congressman talked of the Anti-imperialist League, headed by powerful men like Ex-President Grover Cleveland, Andrew Carnegie, and Justice Joseph Story, which was “spreading fear and indignation by alleging that the Republican Administration, in taking over the Philippines, was embarking on a career of imperialism and wrecking America’s constitutional principles.” The Democratic Party, having promised independence to the Filipinos as early as in the presidential campaign of 1900, announced itself in favor of giving that independence immediately.

“But sir,” Congressman Cooper pointed out, “the Democrats were less interested in the Filipinos than in their own skins. Do you know that their official platform declared. “The Filipinos cannot be citizens without endangering our civilization. . . .’?”

Although by 1902 General Aguinaldo had already been captured in Palana, Isabela, by Colonel Funston, and the backbone of the insurrection had been broken, Filipino guerrillas were still active. Americans and Filipinos were still killing each other and the American press continued to carry lurid and gory tales of alleged Filipino brutalities and atrocities. As a consequence American public opinion was bitterly anti-Filipino.

“Most Americans, including prominent Republicans and Democrats, believed that your people were unfit for self-government,” Congressman Cooper went on. “In fact, many of them, including our leading newspapers and responsible statesmen, were convinced the Filipinos were barbarians, pirates, and savages.”

Then he recalled the day when, as chairman of the house Committee on Insular Affairs, which handled Philippine legislation, and as principal author of the Bill of 1902, he made his sponsorship speech. The date was June 19.

“Soon after I’d started speaking,” he recounted, “gentlemen on both sides of the House stood up and demanded to be heard. They badgered and interrupted me often. Finally I refused to yield the floor. I made a long speech; I covered every phase of the Philippine problem—economic, social, political, and Philanthropic. But the strongest argument which I had to demolish was the claim that the Filipinos were savages unfit for self-government. Therefore, I had to address myself especially to this particular point; and, just as President McKinley looked upon God for guidance, so I called upon your Rizal for support. He didn’t fail me.”

The Congressional record for that day chronicles that Congressman Cooper opened his argument against the detractors of the Philippines as follows?

“Everyday we hear men declare that the people of the Philippines are ‘pirate,’ ‘barbarians,’ ‘savages,’ ‘incapable of civilization’. . . newspapers of prominence have repeatedly endorsed this view.

“Mr. Chairman, I am not here to join in this cry so often hear. . . . Before we say that the Filipino people are barbarians and savages whose future is hopeless, we should remember the past and not forget how largely human beings are the products of environment. . . . Think of their history! For three hundred hopeless years they had seen Spanish officials treat office merely as a means by which to rob the helpless people. For three hundred years they lived under a government which deliberately kept the mass of the people in ignorance, which deliberately sought to close to them every avenue of social and political advancement; a government under which it was well-nigh useless for a man even to attempt to acquire property, because his accumulations furnished only so much more of temptation and opportunity for the rapacity of government officials; a government which punished even the most respectful protest against its infamous executions with banishment or death. . . .

“What the Filipinos think, what they feel what they do, are only the natural results of what they have undergone. Yet, sir, despite this environment, this deprivation, this wrong and contumely and outrage, this unfortunate race has given to the world not a few examples of intellectual and moral worth—men in the height of mind and power of character.”

Then the talked of Rizal:

“It has been said that if American institutions had done nothing else than furnish to the world the character of George Washington, ‘that alone would entitle them to the respect of mankind.’ So, sir, I say to all those who denounce the Filipinos indiscriminately as barbarians and savages, without possibility of a civilized future, that this despised race proved itself entitled to their respect and to the respect of mankind when it furnished to the world and character of Jose Rizal.”

Briefly, he narrated the life of the hero from his birth in Calamba to his sentence to death by a Spanish court-martial in Manila.

“On the night before his death, he wrote a poem,” Cooper continued. “I will read it, that the house may know what were the last thoughts of this ‘pirate,’ this barbarian,” this ‘savage,’ of a race ‘incapable of civilization’!”

With eloquence and feeling, Cooper recited Mi Ultimo Adios as translated into English by Derbyshire. When the last line, “Farewell, dear ones, farewell! To die is to rest from our labors,” had faded away, there was a long, deep silence. Then the entire House broke into prolonged applause.

“Encouraged by the demonstration,” Congressman Cooper continued his narration to me, “I plunged into my climax. Even now I can remember the words; I fairly thundered them:

“Pirates! Barbarians! Savages! Incapable of civilization.’ How many of the civilized, Caucasian slanderers of his race could ever be capable of thoughts like these, which on the awful night, as he sat alone amidst silence unbroken save by the rustling of the black plumes of the death angel at his side, poured from the soul of the martyred Filipino? Search the long and bloody roll of the world’s martyred dead, and where—on what soil, under what sky—did Tyranny ever claim a nobler victim?

“Sir, the future is not without hope for a people which, from the midst of such an environment, has furnished to the world a character so lofty and so pure as that of Jose Rizal.”

Now visibly tired from his memory and oratorical exertions, he rested. Yet, though faintly panting, his seamy face wore more than the suggestion of a smile. He was reliving his years of power and triumph, and he was happy. His next words confirmed what his countenance had already proclaimed.

“The result was a complete triumph for Rizal, the Filipinos and justice,” he said, “and, I think I should add in all candor, myself.”

He stopped to savor the thought with relish.

“The story and poetry of Rizal did something to the House akin to a miracle,” he continued. “Your great patriot made congressmen — as well as senators — forget the Philippine insurrection and remember only your people’s travails. Rizal kindled a light by which, for the first time, Americans had done in 1776. Out of Rizal’s life and labors there was born an American-Philippine kinship that he has endured.” Almost as an after-thought, he added, “In the voting on the bill which followed shortly, American statesmen gave Rizal a sizeable majority: the measure was soon ready for the signature of the President. Theodore Roosevelt for, alas, the gentle McKinley had been assassinated the previous years.

I could not help asking him a question. For even as we were talking the Quezon-Wood quarrel raged in Manila and produced serious repercussions in Washington. “A kinship that has endured, Mr. Congressman?” I inquired rhetorically.

“Don’t ever worry for a moment.” he replied, raising a thin hand in a reassuring gesture. “The basic American policy in the Philippines is embodied in law and honored in practice. It is gradual self-government inevitably leading to independence. Having gathered the momentum of time, there’s no turning it back. Men are mere incidents; America’s policy is a matter of national honor.

“The law of 1902 gave your people their first adequate opportunity to show their political capacity. And your statesmen — Osmeña, Quezon and others — have vindicated your people and justified the faith of those of us who, in 1898-1902, saw in the Filipino with his bolo, not a brute savage, but a man defending his motherland and his freedom. You’ve made good. No American can alter that record — ever.

“And when you’re free at last — and I hope it’ll be before I die — you’ll honor Rizal even more. For he not only awakened the Filipinos and wrote finis to Spanish imperialism but also lighted the way for America.”

The interview was over. Nothing more needed to be said. We shook hands. He sank back in his chair and I turned and left.

Sunday, November 28, 2010

General Arthur MacArthur on Apolinario Mabini 1902

During his examination before the Senate Investigating Committee, Major-General MacArthur made the following statement' in answer to the questions of the Committee:

Mabini to the American People 1899

Article published in American Newspaper after Mabinis capture late Dec 1899.

The following papers by Senor Mabini were originally published in the Springfield (Mass.) "Republican," May 25, 1900. They seem so pertinent at the present time, in view of the renewed discussion of Philippine affairs in Congress and elsewhere, that they are reproduced entire:

Guam Exiles 1901

|

| Exiles during process of deportation to Presidio of Asan, Guam 1901. |

January 14-22 1901

War Report

Names of prisoners and their servants deported to Guam on the transport Rosecrans.

Prisoners:

- Maximino Trias,

- Macario de Ocampo,

- Julian Gerona,

- Francisco de los Santos,

- Apolinario Mabini,

- Arternio Ricarte,

- Mariano Llanera,

- Pio del Pilar,

- Pablo Ocampo,

- Maximo Hizon,

- Esteban Consortes,

- Lucas Camerino,

- Pedro Cubarrubias,

- Mariano Barruga,

- Hermogenes Plata,

- Cornelio Requestis,

- Fabian Villaruel,

- Juan Leandro Villarino,

- Jose Mata,

- Ygmidio de Jesus,

- Alipio Tecson,

- Pio Varican,

- Anastasio Carmona,

- Lucino Almeida,

- Simon Tecsou,

- Silvestre Legaspi,

- Juan Mauricio,

- Doroteo Espina,

- Bartolome de la Rosa,

- Norberto Dimayuga,

- Jose Buenaventura,

- Antonio Frisco Reyes.

Servants:

- Maximiano Clamor,

- Adel Magcalas,

- Juan Guan,

- Faustino de los Santos,

- Prudencio Mabini,

- Aguitino Gandeza,

- Benito de Nuya,

- Jos6 Jabier,

- Manuel Rivera,

- Antonio Brimo,

- Vicente Antiguera,

- Joaquin Agramon (a prisoner),

- Esequial de los Santos,

- Juan Guasay,

- Euligio Gonzales (a prisoner).

---

Generals: Arternio Ricarte, Mariano Llanera, Pio del Pilar, Maximo Hizon, Francisco de los Santos,

Colonels: Macario de Ocampo, Esteban Consortes, Lucas Camerino, Julian Gerona,

Lt Colonels: Pedro Cubarrubias, Mariano Barruga, Hermogenes Plata, Cornelio Requestis,

Major: Fabian Villaruel,

Subordinate Officers: Juan Leandro Villarino, Jose Mata, Ygmidio de Jesus, Alipio Tecson,

Civil Officials, insurgent agents, sympathizers, and agitators: Apolinario Mabini, Pablo Ocampo, Maximino Trias, Simon Tecson, Pio Varican, Anastasio Carmona,

**Mariano Sevilla, Manuel E. Roxas...listed with Civil Officials, insurgent agents, sympathizers, and agitators.

Others

Jan 14 - Lucino Almeida...tried as insurgent of San Fernando de la Union

Jan 15 - Solace - Ilocos Norte..belong to Katipunan Society. Sylvestre Legaspi, Juan Mauricio, Doroteo Espino, Bartolome de la Rosa, Norberto **imayuga[cut], Jose Buenaventura, and Antonio Prisco Reyes.

Jan 22-24th

10 transported on the Solace

Listed as Civil Officials, insurgent agents, sympathizers, and agitators

- Roberto Salvante

- Pancracio Palting

- Gavino Domingo

- Florencio Castro

- Inocente Cayetano

- Marcelo Quintos

- Jayme Morales

- Leon Flores

- Pedro Erando

- Pancracio Adiarte

- Faustino Adiarte

Camp at Presidio of Asan

Can not go east of the east gate...more 50 yards.

Can not go west of the 1st bridge.

Can not go south of the Agana-Piti Road...more than 100 yards.

And north to the seashore.

*Presidio of Asan previously used as a Leper colony(1892-1900)

1898 Exiles - Hong Kong Junta

In this Photo:

General Mariano Llanera,

General Vito Belarmino,

Dr. Anastacio Francisco,

Celestino Espinosa,

General Manuel Tinio,

Pedro Paterno,

Escolastico "Lino" Viola,

Miguel Primo de Rivera,

Agapito Bonzon,

General Wenceslao Viniegra,

Emilio Aguinaldo,

General Gregorio Del Pilar,

Joaquin Pezzi,

Antonio Montenegro,

Primitivo Artacho,

General Benito Natividad,

Maximo Kabigting,

Maximino Paterno,

Melecio Carlos,

General Tomas Mascardo

Mariano Llanera, Tomas Aguinaldo, Vito Belarmino, Antonio Montenegro, Escolastico Viola, Lino Viola, Valentin Diaz, Dr. Anastacio Francisco, Benito Natividad, Gregorio H. del Pilar, Manuel Tinio, Salvador Estrella, Maximo Kabigting, Wenceslao Viniegra, Doroteo Lopez, Vicente Lukban, Primitivo Artacho, Tomas Mascardo, Joaquin Alejandrino, Pedro Aguinaldo, Agapito Bonson, Carlos Ronquillo, Teodoro Legazpi, Agustin de la Rosa, Miguel Valenzuela, Antonio Carlos, Celestino Aragon, Jose Aragon, Pedro Francisco, Lazaro Makapagal y Lakang-dula, Silvestre Legazpi, Vitaliano Famular, Vicenter Kagton, Francisco Frani, Eugenio de la Cruz, and Miguel Malvar.

G. Vito Belarmino, Heneral ng dibisiyon at pangsamantalang direktor de guerra.

G. Antonio Montenegro, direktor de Estado

G. Mariano Llanera, Tenyente Heneral.

G. Tomas Mascardo, Heneral ng Brigada.

G. Salvador Estrella, Heneral ng Brigada.

G. Lazaro Makapagal at Lakandula, Koronel.

G. Agapito Bonzon, Koronel.

G. Wenceslao Viniegra, Koronel.

G. Benito Natividad, (taga-Nueba Esiha), Koronel.

G. Gregorio del Pilar, Koronel

G. Silvestre Legazpi, Tesorero Heneral.

G. Jose Ignacio Pawa, Tenyente Koronel.

G. Vicente Lukban Koronel Ingeniero.

G. Anastacio Francisco, direktor ng Sanidad.

G. Celestino Aragon, Opisyal ng sanidad.

G. Agustin de la Rssa, idem.

G. Primitivo Artacho, idem.

Dr. Viola, (taga-San Miguel de Mayumo) at saka isa pang nagngangalang Leon Novenario, taga Pateros, na naging ayudante ni "Vibora".

Katipunan Code

Z........A

C........O

N........I

X........U

V........M

LL.......N

J.........L

F.........H

ģ........NG

Sa inyong lahat ipinatutungkol ang pahayag na ito. Totoong kinakailangan na sa lalong madaling panahon ay putlin natin ang walang pangalang panglulupig na ginagawa sa mga anak ng bayan na ngayo'y nagtitiis ng mabibigat na parusa at pahirap sa mga bilangguan na sa dahilang ito'y mangyaring ipatanto ninyo sa lahat ng mga kapatid na sa araw ng Sabado, ika 29 ng kasalukuyan, ay puputok ang pang hihimagsik na pinagkasunduan natin, kaya't kinakailangang sabaysabay na kumilos ang mga bayanbayan at sabaysabay na salakayin ang Maynila. ang sino pa mang humadlang sa banal na adhikang ito ng bayan ay ipalalagay na taksil at kalaban maliban na nga lamang kung may sakit na dinaramdam o ang katawa'y may sama at sila'y paguusigin alinsunod sa palatuntunang ating pinaiiral.

bundok ng kalaayan, Ika 28 ng Agosto ng 1896.

MAYPAGASA

*Other codes exist. Above is one code used by the Katipunan.

Photos complements of Carinoza

The Real Glory 1936 Film

Film can be viewed in its entirety on youtube.

1898 Battle of Dagupan, Pangasinan

Battle of Dagupan, Pangasinan

DAGUPAN CITY -- When the Philippine Independence was proclaimed in Cavite Viejo on June 12, 1898, the province of Pangasinan was still under Spanish sovereignty, till 40 days later following the famous "Battle of Dagupan" from July 18 to 22 of that year.The 'Battle of Dagupan', fought fiercely by local Katipuneros under the overall command of General Francisco Makabulos, chief of the Central and Directive Committee of Central and Northern Luzon, and the last remnants of the once mighty Spanish Army under General Francisco Ceballos, led to the liberation of Pangasinan from the Spaniards.

The five-day battle was joined by three local heroes, Don Daniel Maramba from Sta. Barbara, Don Vicente Del Prado from San Jacinto and Don Juan Quezada from Dagupan, whose armies massed in Dagupan to lay siege on the Spanish forces, making a last stand at the brick-walled Catholic Church.

Unknown to the present generations, the three heroes in the 'Battle of Dagupan' who historians believed were the ones who sparked the flame of revolution in their own province, later emerged to become governors in different times and climes.

Maramba, who became governor of Pangasinan during the American regime, etched his name in the history of the province when he liberated the town of Sta. Barbara on March 7, 1898 following a signal for simultaneous attack from Makabulos.

Maramba was probably the most well-loved and most famous governor that ever ruled Pangasinan till today. Under his direction, Sta. Barbara became the first town in Pangasinan liberated by the Filipinos from the Spaniards.

Schooled at the San Juan de Letran in Manila, from where he joined the Kataastaasan Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan or KKK, Maramba placed the much-astonished Friar Tienza, parish priest of Sta. Barbara, under house arrest and handed the affairs of the parish over to Fr. Cadiz, a Filipino secular priest.

Hearing that Sta. Barbara fell into rebel hands, the Spanish forces in Dagupan attempted to retake the town, but were repulsed by Maramba's forces. Thus, after the setback, the Spaniards decided to concentrate their forces in Lingayen to protect the provincial capital.

This enabled Maramba to expand his operations to Malasiqui, Urdaneta and Mapandan, taking them one after the other. He took one more town, Mangaldan, before proceeding to Dagupan to lay siege on the last Spanish garrison.

Also on March 7, 1898, the rebels under the command of Del Prado, and Quesada attacked convents in a number of towns in Zambales province, located west of Lingayen, which now constitute the western parts of Pangasinan.

Attacked and brought under Filipino control were Alaminos, Agno, Anda, Alos, Bani, Balincaguin, Bolinao, Dasol, Egui and Potot. Then the revolt spread to Labrador, Sual, Salasa and many other towns in the west.

The towns of Sual, Labrador, Lingayen, Salasa and Bayambang were occupied first by the forces of Del Prado and Quesada before they proceeded to attack Dagupan.

At an assembly convened to organize a central governing body for Central and Northern Luzon on April 17, 1898, General Makabulos appointed Del Prado as politico-military governor of Pangasinan, with Quesada as his second in command.

His appointment came few days before the return of General Emilio Aguinaldo in May 1898 from his exile in Hongkong following the signing of the Pact of Biac-na-Bato in December 1897.

In her book, Dr. Rosario Mendoza-Cortez wrote that Aguinaldo's return gave fresh impetus to the renewal of the flame of the revolution. Thus, on June 3, 1898, General Makabulos entered Tarlac and from that day on, the fires of revolution spread.

So successful were the Filipinos in their many pitch battles against the Spaniards that on June 30, 1898, Spanish authorities decided to evacuate all their forces to Dagupan where a last stand against the rebels was to be made.

Also ordered to go to Dagupan were all civilian and military personnel, including members of the voluntarios locales of towns not yet in rebel hands. Those who heeded this order were the volunteer forces of Mangaldan, San Jacinto, Pozorrubio, Manaoag and Villasis.

Among those brought to Dagupan was the image of the Most Holy Rosary of the Virgin of Manaoag, which at that time was already the patron saint of Pangasinan.

When the forces of Maramba from the east and Del Prado from the west converged in Dagupan on July 18, 1898, the siege began. The arrival of General Makabulos strenghtened the rebel forces until the Spaniards, holed up inside the Catholic Church, waved the flag of surrender five days later.

Armed poorly, the Filipinos were no match at the very start with Spanish soldiers holed inside the Church. They just became mere sitting ducks to Spanish soldiers shooting with their rifles from a distance.

But the tempo of battle changed when the attackers deviced a crude means of protection to shield them from Spanish fires while advancing. This happened when they rolled trunks of bananas, bundled up in sawali, that enabled them to inch their way to the Church.

In her book, "Pangasinan: 1891-1900", Dr. Mendoza-Cortez said after the battle on July 22, 1898, all the Spanish provincial officials surrendered and were taken as prisoners of war.

There was so much jubilation in Dagupan and the rest of Pangasinan when the Spaniards surrendered. That was the time the Pangasinenses decided to reenact the proclamation of independence done at Cavite on June 12, 1898.

But the formal ceremony was done five days later on July 28, 1898 when the people assembled at the town plaza to hear the reading of the Act of Proclamation of Independence of the Filipino People which took place at Cavite Viejo on June 12, 1898.

The three heroes in the Battle of Dagupan continued to bear arms even during the Filipino-American War, with Maramba offering his help to General Antonio Luna.

A product of Ateneo de Manila, Del Prado was later elected representative of Pangasinan to the Malolos Congress, with Quesada succeeding him as governor of Pangasinan. During the Filipino-American War, Del Prado again went to war.

On orders of General Aguinaldo in Bayambang dismantling the Philippine Army, Del Prado waged a guerrilla warfare against the Americans. Thus, the latter branded him as a brigand. With the aid of a native bribed by the Americans, Del Prado and his men were captured in Sison.

Pangasinan's foremost historian, Restituto C. Basa, said Del Prado was brought to Dagupan and imprisoned. When the Americans asked for his allegiance to their flag, he spat on it. Thus, he was hanged at the Dagupan City Plaza.

When Aguinaldo retreated to Bayambang, Quesada -- as governor of Pangasinan -- met him. He was among the Pangasinenses who escorted him (Aguinaldo) in his further retreat to the north, culminating at Palanan, Isabela.

But on the way at Bangued, Abra, Aguinaldo reportedLy bade goodbye to his escorts so they could go back home. In his return trip to Pangasinan, Quesada reportedly got sick of malaria and died. (PNA Newsfeatures)

THE TRUE DECALOGUE

"THE TRUE DECALOGUE"

By APOLINARIO MABINI

First. Thou shalt love God and thy honor above all things: God as the fountain of all truth, of all justice and of all activity; and thy honor, the only power which will oblige thee to be faithful, just and industrious.

Second. Thou shalt worship God in the form which thy conscience may deem most righteous and worthy: for in thy conscience, which condemns thy evil deeds and praises thy good ones, speaks thy God.

Third. Thou shalt cultivate the special gifts which God has granted thee, working and studying according to thy ability, never leaving the path of righteousness and justice, in order to attain thy own perfection, by means whereof thou shalt contribute to the progress of humanity; thus; thou shalt fulfill the mission to which God has appointed thee in this life and by so doing, thou shalt be honored, and being honored, thou shalt glorify thy God.

Fourth. Thou shalt love thy country after God and thy honor and more than thyself: for she is the only Paradise which God has given thee in this life, the only patrimony of thy race, the only inheritance of thy ancestors and the only hope of thy posterity; because of her, thou hast life, love and interests, happiness, honor and God.

Fifth. Thou shalt strive for the happiness of thy country before thy own, making of her the kingdom of reason, of justice and of labor: for if she be happy, thou, together with thy family, shalt likewise be happy.

Sixth. Thou shalt strive for the independence of thy country: for only thou canst have any real interest in her advancement and exaltation, because her independence constitutes thy own liberty; her advancement, thy perfection; and her exaltation, thy own glory and immortality.

Seventh. Thou shalt not recognize in thy country the authority of any person who has not been elected by thee and thy countrymen; for authority emanates from God, and as God speaks in the conscience of every man, the person designated and proclaimed by the conscience of a whole people is the only one who can use true authority.

Eighth. Thou shalt strive for a Republic and never for a monarchy in thy country: for the latter exalts one or several families and founds a dynasty; the former makes a people noble and worthy through reason, great through liberty, and prosperous and brilliant through labor.

Ninth. Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself: for God has imposed upon him, as well as upon thee, the obligation to help thee and not to do unto thee what he would not have thee do unto him; but if thy neighbor, failing in this sacred duty, attempt against thy life, thy liberty and thy interests, then thou shalt destroy and annihilate him for the supreme law of self-preservation prevails.

Tenth. Thou shalt consider thy countryman more than thy neighbor; thou shalt see him thy friend, thy brother or at least thy comrade, with whom thou art bound by one fate, by the same joys and sorrows and by common aspirations and interests.

Therefore, as long as national frontiers subsist, raised and maintained by the selfishness of race and of family, with thy countryman alone shalt thou unite in a perfect solidarity of purpose and interest, in order to have force, not only to resist the common enemy but also to attain all the aims of human life.

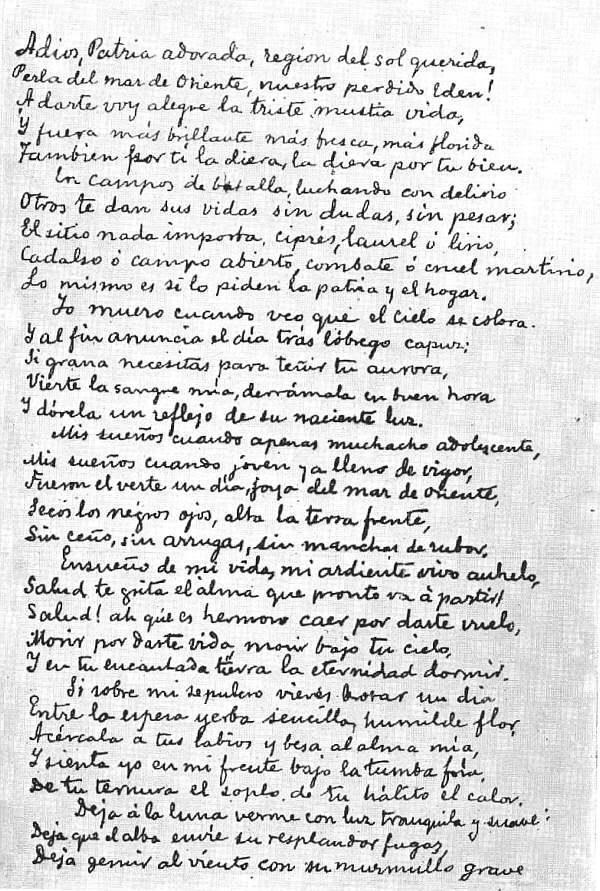

Mi Ultimo Adios

Mi Ultimo Adios

Fort Santiago, Intramuros

Farewell, dear Fatherland, clime of the sun caress'd

Pearl of the Orient seas, our Eden lost!,

Gladly now I go to give thee this faded life's best,

And were it brighter, fresher, or more blest

Still would I give it thee, nor count the cost .

On the field of battle, 'mid the frenzy of fight,

Others have given their lives, without doubt or heed;

The place matters not-cypress or laurel or lily white,

Scaffold or open plain, combat or martyrdom's plight,

It is ever the same, to serve our home and country's need.

I die just when I see the dawn break,

Through the gloom of night, to herald the day;

And if color is lacking my blood thou shalt take,

Pour'd out at need for thy dear sake

To dye with its crimson the waking ray.

My dreams, when life first opened to me,

My dreams, when the hopes of youth beat high,

Were to see thy lov'd face, O gem of the Orient sea

From gloom and grief, from care and sorrow free;

No blush on thy brow, no tear in thine eye.

Dream of my life, my living and burning desire,

All hail ! cries the soul that is now to take flight;

All hail ! And sweet it is for thee to expire ;

To die for thy sake, that thou mayst aspire;

And sleep in thy bosom eternity's long night.

If over my grave some day thou seest grow,

In the grassy sod, a humble flower,

Draw it to thy lips and kiss my soul so,

While I may feel on my brow in the cold tomb below

The touch of thy tenderness, thy breath's warm power.

Let the moon beam over me soft and serene,

Let the dawn shed over me its radiant flashes,

Let the wind with sad lament over me keen;

And if on my cross a bird should be seen,

Let it trill there its hymn of peace to my ashes.

Let the sun draw the vapors up to the sky,

And heavenward in purity bear my tardy protest

Let some kind soul o 'er my untimely fate sigh,

And in the still evening a prayer be lifted on high

From thee, 0 my country, that in God I may rest.

Pray for all those that hapless have died,

For all who have suffered the unmeasur'd pain;

For our mothers that bitterly their woes have cried,

For widows and orphans, for captives by torture tried

And then for thyself that redemption thou mayst gain.

And when the dark night wraps the graveyard around

With only the dead in their vigil to see

Break not my repose or the mystery profound

And perchance thou mayst hear a sad hymn resound

'T is I, O my country, raising a song unto thee.

And even my grave is remembered no more

Unmark'd by never a cross nor a stone

Let the plow sweep through it, the spade turn it o'er

That my ashes may carpet earthly floor,

Before into nothingness at last they are blown.

Then will oblivion bring to me no care

As over thy vales and plains I sweep;

Throbbing and cleansed in thy space and air

With color and light, with song and lament I fare,

Ever repeating the faith that I keep.

My Fatherland ador'd, that sadness to my sorrow lends

Beloved Filipinas, hear now my last good-by!

I give thee all: parents and kindred and friends

For I go where no slave before the oppressor bends,

Where faith can never kill, and God reigns e'er on high!

Farewell to you all, from my soul torn away,

Friends of my childhood in the home dispossessed!

Give thanks that I rest from the wearisome day!

Farewell to thee, too, sweet friend that lightened my way;

Beloved creatures all, farewell! In death there is rest!

Death of General Gregorio del Pilar

December 2, marks the 106 anniversary of the Battle of Tirad Pass led by the youngest and what historians are wont to rhapsodize as "the most picturesque" Filipino generals of the revolution, Gregorio del Pilar.

It was at the peak of the mountain pass in Northern Luzon that 60 Filipino soldiers carried out a heroic stand against American troops in the morning of ..hus enabling President Emilio Aguinaldo to flee towards the "wilds of Lepanto." Sadly, however, 52 of them including Del Pilar, then 24, perished in what an American war correspondent dramatically termed as a "battle above the clouds."

The awesome story has been told and retold with epic grandeur, how Del Pilar stood with his valiant soldiers on the steep and solitary mountain Pass of Tirad, steadfast to repel the invader, or fight and die like honorable men. In a moving eulogy delivered on the occasion of the delivery of the remains of Del Pilar to the National Museum on Dec. 2, 1930 31 years after the historic battle, Benito T. Soliven, then Representative of the First District of Ilocos Sur, observed that the Filipino soldiers "stand against overwhelming odds has been fittingly compared by American contemporary writers to that of Leonidas and his Spartans at Thermopylae, and that of the embattled Afridis at Dargai Ridge. Even now, we are thrilled with the account of their courage. But the death of Del Pilar is something more than a soldiers death. It was the sublime protest of a patriot against the decree of adverse fate. He had yearned for death when he saw that all was lost for the Republic. He had wished for it when long before the battle of Tirad, he proposed to meet the pursuing enemy after the disaster at Caloocan. He felt its obsession when at midnight on the bank of the river at Aringay he woke up his soldiers and pointedly asked them this question: Brothers, which do you prefer, to die fighting or to flee like cowards?

"From morning till noon he repelled charge after charge, he tenaciously held on with his handful of men through the heat and agony of battle, till he himself fell dead among his slain soldiers. And well chosen and most fitting was the place where he offered the sacrifice of his life. It was on the mountain summit, overlooking the plains and the shores of his country, a massive and tremendous altar, built as it were for Titans, caressed by the rolling clouds of morning, lighted by the stars of dusk."

Admittedly, it was one of the darkest hours in Philippine history. President Aguinaldo was retreating to the mountains with only a few faithful followers about him. The young general could not bear to see the misfortune of his country. A man of iron who could not yield to the foe like Andrs Bonifacio and Antonio Luna, Del Pilar could accept no compromise.

Men of their caliber are worthy of our admiration. For noble and worthy causes that will enrich national well-being, they fight to the death with manly devotion and true heroism. In moments of need and times of great emergencies such as today, the entire Filipino nation can always draw lessons from their selfless sacrifices.

Art has a way of either lionizing heroes through copious commemorative monuments and/or murals or relegating them to almost a state of oblivion because of the paucity of visual materials on them.

Take the case of Gregorio Del Pilar. How has Philippine art treated him?

While it is a true that there had been a movie about him recently which starred the once-upon-a-time teen heartthrob Romnick Sarmenta, one can still count on his fingers the instances where his visage adorned nationally heralded paintings or sculptures. Of the few existing examples, two can be found at the University of the Philippines Diliman Main Library.

"Tirad Pass: Ably Defended by General Gregorio del Pilar" by Ramn Resurreccin Peralta reflects the orientation of the painter as a scenographer, Peralta being the leading scenographic painter after Toribio Antillon during the early 1900s.

Painted 32 years after the battle at Tirad Pass, the artwork is a vivid interpretation of the pass as described in history books. Its huge background shows the rugged terrain of Mt. Tirads trail. The figure of Del Pilar, in full military regalia and mounted on a horse, is rendered relatively minute in this painting.

In contrast to this painting is Carlos Perez Valino Jr.s "General Del Pilar at Tirad Pass" where the image of the fallen hero looms large in the composition.

Valino, best known for his history paintings that portray events like Lapu-Lapus victory over Magellan, Limahong, scenes of the revolution against Spain and the Japanese Occupation, was commissioned in 1964 by UP President Carlos P. Romulo, to paint Del Pilar a tribute.

The result was a huge easel painting, all of 198.5 by 346.5 cm, showing the young general on horseback and brandishing his sword depicting the general turning towards the narrow trail of Tirad Pass, visible behind him. The entire scene is enveloped in gray smoke.

Whereas Peraltas work is about the rugged Tirad Pass, with Del Pilar as a gallant knight exploring what the trail offered, Valinos work is about the harsh reality of an insensitive war, devoid of human compassion.

Another painting dealing with the same subject is Vicente Alvarez Dizons "Battle of Tirad Pass." Sadly however, the paintings provenance remains unknown until the present. When it was first shown, it generated quite a controversy because it depicted Del Pilar shooting an American soldier, which, according to historians, was never recorded in history books. Dizon reasoned out, however, that he relied on personal accounts of eyewitnesses and participants he himself interviewed prior to the painting of the work. In fact, many of the faces included in the historical painting are portraits of those who survived the encounter to tell their stories. The painting, done in 1931, is contiguous to Peraltas "Tirad Pass: Ably Defended by General Gregorio del Pilar," also done the same year.

The same image and narrative are also committed to sculpture. The likeness of Gregorio Del Pilar was executed in 2000 into an equestrian statue by history sculptor Apolinario Paraiso Bulaong.

The larger than life equestrian sculpture stands at the very site of the battle at Tirad Pass, ending the long drought to realize Joint Resolution No. 6 passed by the Philippine Legislature in 1939 providing for the erection of a monument on the spot where Del Pilar fell if only to preserve the glorious and historic event in the mind and memory of the Filipino people.

It was Mayor Anacleto Meneses of Bulacan, Bulacan who commissioned Bulaong to execute the sculpture. The piece was donated by the mayor to the municipality of General del Pilar in Ilocos Sur, formerly known as Concepcion. Concepcion and Bulacan are sister towns.

Aside from this equestrian statue and numerous bust portraits of Del Pilar, Bulaong also executed in 2001 a relief sculpture depicting the battle at Tirad Pass. The sculptural mural is installed at the plaza of Bulacan, Bulacan, where Del Pilar came from.

While working on the grand manner of history, art may have lost its popular appeal in contemporary times, but it still presents a challenge to young Filipino artists to continue with the tradition. One of the lofty functions of art that certainly will not perish is its poignant capacity to edify life. And for this, history painting and history sculpture remain the quintessential art forms to explore.

The Philippine Flag - its Masonic Roots

Time and again it has been asserted that masonry played an important role in the design of the Philippine flag and that some of its symbols were meant to memorialize the Craft. These assertions are essentially plausible, for the man principally responsible for its design — President Emilio Aguinaldo — was a zealous masonic partisan. In one of his speeches delivered after the Revolution, Aguinaldo said; "The successful Revolution of 1896 was masonically inspired, masonically led, and masonically executed. And I venture to say that the first Philippine Republic of which I was its humble president, was an achievement we owe, largely, to masonry and the freemasons." Speaking of the revolutionists, he added; "With God to illumine them, and masonry to inspire them, they fought the battle of emancipation and won." During the Revolution, Aguinaldo frequently displayed a marked bias in favor of freemasons and masonry. He made membership in the masonic fraternity an important qualification for appointments to government positions. His nepotism was so pronounced, a critic of masonry denounced it as one of the "evils" of the Revolution. In his Memoirs, Felipe Calderon, the President of the Malolos Congress, claimed that the "sectarian masonic spirit" undermined the insurrection. He also argued that some serious dissensions among Filipinos originated, "more than for anything else, from the mania of Aguinaldo, or rather of his adviser, Mabini, to elevate any person who was a mason" It should not come as a surprise to anyone, therefore, if Aguinaldo decided to extol masonry in the Philippine flag.

Some of the claims made in favor of the masonic link of the Philippine flag, however, are so lavish they strain the reader's credulity. If all are to be accepted at face value, we cannot avoid the conclusion that our national emblem is a clone of the masonic banner and that all the devices and symbols used in it are of masonic origin, from the triangle, to the sun and stars, down to its colours. The lavish claims, however, were made by freemasons and, therefore, the possibility of exaggeration or embellishment, owing to over enthusiasm, cannot be discounted. Moreover, Aguinaldo did not make a written affirmation of the masonic connection of the flag. On the contrary, some of his official statements do not jibe with the exceedingly generous assertions of the freemasons. A close scrutiny of the claims in favor of Freemasonry must, therefore, be undertaken. But first let us describe the Filipino flag.

The Hong Kong designed flag that Aguinaldo brought with him from his exile on board the US dispatch boat McCullock, and which became the official flag of the first Philippine Republic, consisted of two horizontal stripes, blue on top and red below. It had a white equilateral triangle at the hoist that is smaller than that in our flag today. Within the triangle, at its center, a mythological sun was depicted with eyebrows, eyes, nose and mouth in black, bearing eight rays without any minor ray for each, and three five-pointed stars, one at each angle of the triangle. All these devices were in gold or yellow colour.

Shortly after its landing on Philippine soil, the flag saw a baptism of fire and blood in several combats with Spanish colonial troops. On June 12, 1898, it was officially consecrated as our national flag at the ceremonial Proclamation of Independence held at Kawit, Cavite. The signer of the proclamation took their oath of allegiance saying: "The undersigned solemnly swear allegiance to the flag and will defend it to the last drop of their blood."

The Aguinaldo flag served as our national emblem up to the conquest of our country by the Americans. During the American régime, the display of the Philippine flag was proscribed from 1902 to 1919. In October of 1919, the ban was officially lifted, but seventeen years of non-use blurred memories about its details. The generation born under the aegis of the new dispensation was unfamiliar with the flag and the few samples that survived were either tattered, faded or termite-eaten. Hence, when Philippine Flag Day was observed on October 30, 1919, there was no uniformity in the design of the Filipino flag. Any tricolour with or without the sunburst device and three stars within a white triangle was taken as the Filipino flag. For well over a decade the confusion surrounding the design of the flag persisted.

To do away with irregularities and discrepancies, President Manuel L. Quezon issued Executive Order No. 23, on March 25, 1936, specifying the different elements of the flag. Quezon not only set a uniform pattern for the making of our national emblem as to the size and arrangement of its symbolic elements, he also caused major amendments of its features, to wit:

the mythological sun was changed to a solid golden sunburst without any marking;

the eight single rays in Aguinaldo's flag replaced by eight major rays with two minor beams for each ray;

the size of the equilateral triangle was made larger by making any side equal to the width of the flag at the hoist; and

the colour blue in the upper stripe was standardized to dark blue.

Let us now evaluate the statements that postulate the link between the flag and masonry, viz a viz official announcements on the origin and meanings of the flag's symbols.

Masonic Claims -

Among the more credible assertions relied upon to establish the tie between masonry and the flag are the following:

In October 1899, Ambrocio Flores, Grand Master of the Gran Consejo Regional and at that time a general in the army of Aguinaldo, wrote letters to the Grand Lodges in the United States appealing to them to employ their influence to help the fledgling Philippine Republic. In these letters he compared the Philippine flag to the masonic banner saying, "...this national flag resembles closely our masonic banner starting from its triangular quarter to the prominent central position of its resplendent sun surrounded in its triangular position by three 5-pointed stars. Even in its three coloured background, it is the spitting image of our Venerable Institution's banner so that when you see it in any part of the world, waving with honor amidst the flags of other nations and acknowledged by these nations, let us hope that with this flag, and through it, our common parent, Freemasonry will likewise be so honored."

In his beautiful Grand Oration pronounced in 1928, historian Teodoro M. Kalaw, Sr., uttered these words: "And the triangle appearing on the Philippine flag, the loftiest symbolism of the struggles of the Filipino people, was put there, according to President Aguinaldo, as an homage to Freemasonry."

Felipe Calderon, writing with a pejorative and anti-masonic tone, said in his Memoirs:

It is not a secret to any person that one of the causes of the Philippine insurrection against Spain, ... was the animosity of the people ... against the religious corporations .... As a result of this animosity against the religious corporations, a tendency which we might call anti-Catholic developed in certain organizations and individuals of the Revolution so that masonry considered the insurrection, and therefore also the revolution , as it own work and even put the triangle in the Filipino flag. As I have already said, this was an evil that had a noxious influence upon the entire body of the Revolution, because Mabini and its followers considered every mason as qualified to carry out any undertaking, and at that time membership in a masonic lodge was the best recommendation a man could possess.

In the Question and Answer column of the April 1929 issue of The Cabletow, there appeared the following:

Question - The statement was frequently made that the triangle, sun, and stars in the Philippine flag are of masonic origin. This same statement, made by the managing editor of the CABLETOW in a lecture delivered by him, has lately been repeated in Bro. Emmanuel A. Baja's book entitled "Our Country's Flag and Anthem." Having heard the correctness of this statement doubted, I would like to know on what authority it is based.

Answer. - The Editor of this column has heard this statement made by several freemasons who can be considered authorities on the subject, including Wor. Bro. Emilio Aguinaldo, erstwhile president of the Philippine Republic, Bro. Tomas G. del Rosario, M. W. Bro. Felipe Buencamino, and several others. x x x."

PGM Emilio Vitara, a long time private secretary of President Aguinaldo, revealed that Aguinaldo personally acknowledged the indebtedness of the Philippine flag to masonic emblems and symbols.

Official and semi-official explanations of the symbols -

Ranged against the forgoing claims, are the following official and semi-official pronouncements relative to the symbols in the flag: In the Proclamation of Philippine Independence signed in 1898 by Aguinaldo and 96 other Filipino leaders, which consecrated the Hong Kong-designed flag of Aguinaldo as the national emblem of our country, it was stressed:

The white triangle represents the distinctive emblem of the famous Katipunan Society, which means of its blood compact suggested to the masses the urgency of insurrection, the three stars represented the three principal islands of the Archipelago, Luzon, Mindanao and Panay, wherein this revolutionary movement broke out: the sun represents the gigantic strides that have been made by the sons of this land on the road to progress and civilization: its eight rays symbolize the eight provinces: Manila, Cavite, Bulacan, Pampanga, Nueva Ecija, Bataan, Laguna and Batangas, which were declared in a state of war almost as soon as the first revolutionary movement was initiated; and the colours blue, red and white, commemorate those of the flag of the United States of North America in manifestation of our profound gratitude towards that great nation for the disinterested protection she is extending to us and will continue to extend to us.

In a speech before the Malolos Congress, Aguinaldo added the following nationalistic interpretation of the meaning of the three colours of the flag:

Behold this banner with three colours, three stars and a sun, all of which have the following meaning: the red signifies the bravery of the Filipinos which is second to none, a colour that was first used by the revolutionists of the province of Cavite on the 31st of August 1896, until peace reigned with the truce of Biak-na-Bato. The blue signifies that whoever will attempt enslave the Filipinos will have to eradicate them first before they give way. The white signifies that the Filipinos are capable of self-government like other nations… The three stars with five points signify the islands of Luzon, the Visayas, and Mindanao…And, lastly, the eight rays of the rising sun signify the eight provinces of Manila, Bulacan, Pampanga, Nueva Ecija, Morong, Laguna, Batangas and Cavite where martial law was declared. These are the provinces which give light to the Archipelago and dissipated the shadows that wrapped her… By the light of the sun, the Aetas, the Igorots, the Mangyans, and the Moslems are now descending from the mountains, and all of them I recognize as my brothers.

Further explanation was supplied by a letter, dated 6 September 1926, from Carlos Ronquillo, the then private secretary of Aguinaldo, addressed to Emmanuel A. Baja.

The sun I am referring to ... was the mythological sun with eyes, eyebrows, nose and mouth. It was not the artistic one nor the Japanese sun. It was the same sun which appears on the flag of some South American Republics. And I can assure you of this because I drew the design myself by order and instruction of the President, General Aguinaldo.

The adoption of the sun was resolved in order that the flag of the Katipunan could be transformed into "the flag of the republic" sustained and defended heroically not only by the Katipunan men but also by the whole people who had joined the Revolution which was started by the worthy "Association of the Sons of the People."

A few months before the Peace of Biak-na-Bato, the Battalion of Pasong Balite, whose commander was the brave gallant General Gregorio H. Del Pilar, had adopted as their ensign a flag which much resembled the present national flag. It had a blue triangle without a sun or stars, the upper half portion was red and the lower half was black. Like the present Philippine flag, its general outline was inspired also by the Cuban flag.

From these statements it would seem that the devices in the flag were adopted for reasons other than paying homage to Freemasonry. Only the triangle is traceable to Freemasonry through the Katipunan which itself was admittedly and unabashedly patterned after Freemasonry. Even the models would appear to be not the masonic banner, but the flags of Cuba, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay. With all these as a backdrop, let us now evaluate and examine the contentions of the freemasons.

The letter of Flores -

The assertion of Ambrocio Flores that the Filipino flag was a spitting image of the masonic banner definitely packs a lot of weight. As a General in the army of Aguinaldo, Flores was familiar with the Filipino flag, and as Grand Master of the Gran Consejo Regional he was also thoroughly conversant with the masonic banner. He, therefore, knew what he was thinking about when he compared the flag of the masonic banner. Unfortunately no document has come down to us that corroborate the statement of Flores. His claim, therefore, cannot be verified.

The triangle -

The loftiest and most sublime symbol of masonry in the days of the Revolution was the equilateral triangle. The masonic ritual called it the most perfect figure that could be drawn with lines and regarded it as an appropriate emblem of perfection or divinity.

The triangle was the first masonic object shown to a candidate for the admission into the mysteries of the craft. Prior to initiation he was brought to a chamber of reflections by the "Terrible" and placed in front of a table upon which was laid a triangle. Here he was obliged to answer questions concerning his concept of man's duty to God, to himself and to his fellowmen. Inside that lodge the triangle was everywhere. It was on aprons worn by all the officers and members. Stone triangles were placed upon the throne of the "Venerable Maestro" (Worshipful Master) and on the altars of the "Prime Vigilante" (Senior Warden) and the "Segundo Vigilante" (Junior Warden). The tables of the Senior and Junior Wardens and the "Limosnero" (Almoner) were triangular in shape and so were the stools provided for the initiates. The perfect ashlar was represented by a "cubico pyramidal." And the noblest emblem in the lodge, the one which is equivalent to today's letter "G" suspended in the East in all lodges, was the "Delta Sagrada" (Sacred Triangle) with the name of the Great Architect of the Universe inscribed in the center in Hebraic characters.

The triangle also appeared constantly in masonic communications. Many words frequently employed in documents, like taller, logia, hermano, Venerable Maestro, bateria, Salud, Fuerza y Union, were abbreviated and the abbreviations ended not with single dot but three dots arranged in a form of triangle.

In as much as the triangle was the heavyweight among masonic emblems, it became the favorite symbol of the freemasons, including Aguinaldo. This is the symbol the freemasons inscribed on their rings, cuff-links and other jewelries. Aguinaldo, for his part, used it repeatedly in his letters and documents. He incorporated it in the postage and telegraph stamps issued by his government and on the coins which he ordered minted. Even the insignias on the chevrons of the officers of the Revolution bore the triangle. In social gatherings Aguinaldo never forgot the triangle. On his 31st birthday (22 March 1900), he served lunch to his guests in his mountain hideout on a "triangular table for 150 persons." When the anniversary of the ratification of Philippine independence by the Malolos Congress was celebrated in Palanan, Isabela on 29 September, Aguinaldo again tendered lunch for the celebrants on a huge triangular table that could seats 200 persons. Years later, when he entertained his guests in the spacious yard of his mansion in Kawit, Cavite after his installation as Master of his lodge, had all the tables where food was served arranged in the form of a giant triangle.

The Spanish authorities were also aware of the importance placed by freemasons upon the triangle. Its discovery on any document was taken as a dead give-away that it was masonic. Thus, among the pieces of evidence accepted as proof of the guilt of the Thirteen Martyrs of Cavite, were a booklet with a triangle on its frontispiece and a large photograph confiscated from Hugo Perez, the Master of España en Filipinas lodge in Cavite containing several pictures of the members of his lodge arranged in triangular form.

In light of the important role the triangle played in masonic rituals and symbolism it would be the logical and natural choice of any endeavor to pay tribute to Freemasonry. Taking into account Aguinaldo's ardent love affair with the masonic triangle, and considering further that the claimed masonic tie of the triangle in the Filipino flag does not collide with official explanations of the symbols in the flag, and considering, finally, that even a masonic critic in the person of Calderon asserted that the triangle was included in the flag by freemasons, I submit we can accept the statement which Kalaw attributed To Aguinaldo that the triangle in the flag was placed there as a tribute to masonry. The Sun, Stars, and Colors - The sun, stars, and colours red, white and blue are minor emblems in the pantheon of masonic symbolism. They were overshadowed by the square, compasses, level, plumb, etc. The only place were the sun, stars, and the three colours had a degree of importance was in the "Decoracion de la Logia" (Decoration of the lodge).

The rituals of the Grand Oriente Español most emphatically stated that the lodge was a representation of the universe. It directed that the lodge be rectangular in shape and its four walls be denominated East, South, West and North. In the East it was required that a "disco radiante" (radiant disk) be placed representing the sun. Rays radiated from the East, diminishing in brilliance until they reached the West where they were convered with clouds. The ceiling was painted to represent a starlit sky. Stars were also used on the fingers of the canopy covering the throne of Venerable Master. Likewise the altar was draped with red velvet on which was embroidered the square and compasses with a five-pointed stars in the center. Furthermore, a five-pointed star, with the letter "G" in the center, was the symbol of the fellow craft degree.

Red and blue were the dominant colours in the lodge. The walls of the lodge were draped with blood red colour (colgaduras encarnadas) and the altars of the Wardens, the tables of the Orator, Secretary, Treasurer and Almoner, the long benches, the stools for initiates, and all the chairs in the lodge were upholstered or covered with red. On the other hand, the canopy covering the throne of the Worshipful Master was sky blue and even the ceiling of the lodge had a hint of blue. To a Master, therefore, sitting upon his throne, the colours which he saw if he looked straight ahead or to either side was red, and blued if he looked up. Also, the banner which the Statues prescribed for the Federation of the Gran Oriente Español had a blue stripe on top and a red one at the bottom. That for a Blue lodge was blue and the one for a Chapter of Rose Croix was red.

If we give a free reign to our imagination, a similarity between the decoration of the lodge and the Filipino flag could easily be perceived. But imagination cannot be the basis for the historicity of the masonic heritage of the flag. Moreover, it is doubtful if Aguinaldo in those days ever saw a lodge decorated in strict accordance with the specification of the ritual. Masonic meetings were then held on the run, because of the persecution of freemasons by the Spanish colonial powers. Meetings had to be kept secret from profane eyes and were moved from one place to another to avoid detection. Even the triangular tables and other paraphernalia had to be so designed that they could be dismantled and rearranged at a moment's notice to resemble ordinary furniture. For freemasons to have painted the walls and ceiling of their meeting place in conformity with ritual would have been the height of imprudence. The most that can therefore be said is that Aguinaldo must have been aware of the prescribed decoration of the lodge through the rituals with which he was undoubtedly familiar.

In conclusion, I submitted that of all the symbols and devices in the flag it is only the triangle whose masonic parentage may be accepted. The basis for the masonic link of the sun, stars, and colours of the flag are too slim to make out a solid case. But the presence of even only one masonic symbol in the flag should make freemasons proud. After all, it was the premier symbol of the Craft — the symbol of perfection — that was selected for inclusion.

The masonic connection of the Philippine flag does not end with its design. Freemasons have played significant roles during the most memorable events where the flag has been unfolded on Philippine soil. On June 12, 1892, when Philippine independence was proclaimed at Kawit, Cavite a Proclamation of Independence, written by freemason (Ambrocio Rianzares Bautista) and signed by another mason (Aguinaldo), was read. Thereafter a freemason (Rianzares Bautista) displayed the flag before the populace. On October 14, 1943, Philippine Independence was proclaimed anew under the sponsorship of the Japanese Imperial forces. A freemason (Jorge B. Vargas of Sinukuan lodge) read the proclamation terminating the Japanese Military Administration and thereafter another freemason (Aguinaldo) hoisted the flag marking the first time since the start of the Japanese occupation that the flag was displayed in public. On July 4, 1946, for a third time, Philippine independence was announced to the world. On this occasion a Proclamation signed by a mason (President and PGM Harry S. Truman) was read by another freemason (Paul V. McNutt) at the Luneta after which a third freemason (President Manuel A. Roxas, Past Master of Makawiwili lodge No. 55), raised the Philippine standard.

Considering the historic link between the Philippine flag and Freemasonry, no one should begrudge the freemasons of the Philippines if they behold our flag with unbounded pride. To Philippine freemasons, the flag is not only an emblem of liberty and a symbol of the valour and sacrifices of our people, it is also a memorial to the fraternity which they so dearly loved.

Text provided by MW Bro. Reynold S. Fajardo, PGM, GMH. Grand Secretary, Grand Lodge of the Philippine, 2004/11/15

http://freemasonry.bcy.ca/symbolism/philippine_flag.html